by Chris Clark

Promoting a proper balance with nature

Nature and farming are inevitably closely related. Bad farming practices can easily degrade the natural environment and some aspects of farming have a reputation for passing-on the costs of rectification to other parts of the economy, for example re-storing water quality. Promoting a better balance between farming and biodiversity can only come when the evaluation of natural benefits can be quantified on an agreed basis and replace dependence on qualitative and widely disputed measures.

Natural capital

The benefits of ‘nature’s bounty’

In livestock farming, energy from the sun produces grass which then feeds livestock for meat production. Grass can be seen as being supplied to farmers as a ‘free-issue’ commodity in return for land ownership or tenancy. This gives competitive advantage to the farmer which is manifested in unit costs of production. If substitutes for grass are used, these will involve come at some ‘real’ extra cost. In general, making use of nature’s bounty improves profitability of the business.

Revenues can be converted into an equivalent capital sum by using an annuity factor; this equivalent capital sum is the value of the natural capital prevailing in a business at that time.

The concept of nature as a stakeholder

A shareholder in a business typically invests capital in the expectation of a dividend as a reward. The provision of dividend income is an implied obligation of the business and will be a burden on its profits. In recent years it has become normal practice to recognise the importance of customers, suppliers, and employees in a business by treating them, alongside shareholders, as stakeholders.

In any farming business, nature must be a stakeholder, but it is a stakeholder with a difference. Instead of placing a burden on profits to deliver a dividend, it provides benefits such as natural grass, on a ‘free-issue’ basis.

The more productive nature is, the greater the benefits will be to the business. If the degradation of nature reduces its productivity, this would be the equivalent of working against stakeholders’ interests (and constitute a self-inflicted penalty).

Fitting in with accounting conventions

The table below sets out a typical balance-sheet and how this might be adapted to account for natural capital and for nature as a stakeholder. The starting point is the recognition that stakeholders’ interests are a liability on the balance-sheet and that as nature behaves in a opposite fashion to a shareholder, it must rank as a ‘negative liability’.

Balance sheet conventions

Traditional construction

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Fixed Assets - Land - Buildings - Plant and Machinery | Shareholders’ Equity - Subscribed Capital - Retained Profits |

| Current Assets - Stock and Work-in-Progress - Accounts Receivable (Debtors) - (less Accounts Payable/Creditors) | Obligations to Lenders - Long-term Debt - Short-term Overdrafts |

| Intangible Assets - Reputation - Goodwill | |

| Net assets employed | Net liabilities incurred |

| Modifications to Account for Nature | |

| (Natural Capital Assets) | (Nature’s Equity) |

Notes:

The modified value of the net assets employed is reduced compared to the more traditional calculation. This makes it easier for a farming business to deliver a specific Return on Total Assets (ROTA) performance. This phenomenon goes some way to justifying why the most productive farmland sells at a premium, which appears to fly-in-the-face of generally poorer returns in relation to other sectors of the economy.

The annuity factor

Setting an appropriate annuity factor to compute a natural capital equivalent of nature’s bounty is ultimately a matter of judgment for the financial sector. It is comparable to a price/earnings ratio (P/E) and these are driven by profit expectations and an adjustment for factors affecting the quality-of-earnings prevailing in a sector.

Farming has an intrinsically low quality-of-earnings, as profits can vary enormously from one year to another (particularly as a consequence of the weather). A factor of 2.5x has been adopted and this compares with an industrial business of average performance of 5x and some fashionable internet-stocks of 20x.

Environmental stress as an economic indicator

The concept of environmental stress

Farming in the UK lives in a largely managed landscape. It has been progressively modified, for good and ill, for more than 400 years. This landscape was broadly in balance with nature, however, some practices introduced since 1945 have degraded a growing proportion of the farming landscape.

The economic role of farming is to harness natural resources and to do so at a commercial profit. When nature supports maximum levels of profitability, the value of the natural capital employed is also maximised. This is then the long-run stable position for nature. If nature is degraded or compromised, profitability will be reduced, and the value of natural capital employed will also be reduced. In such cases the physical asset (associated with nature) can be seen to work harder for less economic benefit.

The key relationship between stress and Maximum Sustainable Output (MSO)

Profitability, which is the level of profits in relation to the value of outputs, must be differentiated from absolute profits. Profitability is maximised at the MSO point – that is the point at which Corrective Variable Costs (CVCs) are eliminated. In contrast, absolute profits are maximised at the break-back point (where profitability has retreated to zero) – and this position is both unstable and more stressful to the environment.

Natural capital delivers its greatest value at the MSO point and if, as a result of the elimination of CVCs, Nature is considered to be in equilibrium with farming at this point, then the stress on the natural environment must be minimised.

The concept of an Environmental Stress Index (ESI)

Mathematically, as the value of a parameter measuring natural capital is maximised, the inverse of the parameter is being minimised. Therefore, a parameter based on the inverse of a natural capital measure would be a surrogate for levels of environmental stress.

Such an ESI has been defined based on the model set out below:

The Environmental Stress Index (ESI)

Notional Natural Capital (NNC) =

Farm profits x Annuity Factor (of 2.5x)

ESI = log(GTq/NNC)

Where

G = Universal scaling factor to put ESI’s into useable values

T = Topographical rating = Elevation * Latitude/Acreage

Q = Quality rating based on cover-type categories

A log scale is used (as with the Richter scale)

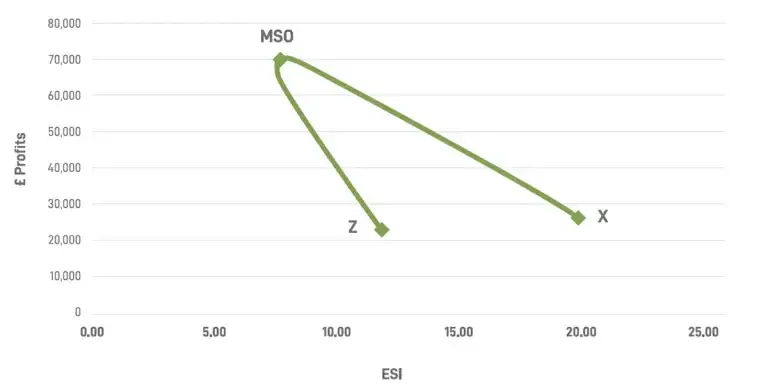

Using the model set out in the table below, ESIs can be computed for farms operating at actual outputs, MSO levels, and zero outputs. This is shown in Table 3, where X is the ESI point at actual output, MSO is the ESI point at MSO, and Z is the ESI point at zero output. It will be seen that ESI is minimised at MSO, while profits are maximised.

Typical pattern of behaviour for an Environmental Stress Index (actual case)

Observations on de-stocking/re-wilding

The managed landscape

At the MSO point, profitability is maximised, the ESI is minimised, and the managed landscape is in a state of stable equilibrium. Small changes on either side of the MSO point will result in an increase in the ESI. This appears to be counter-intuitive in the case of downsizing from the MSO point and it has significant implications for the mechanisms of re-wilding.

All forms of change in a system from one state of affairs to another will result in a change of ‘entropy’. Entropy is essentially a measure of disorder but in a pragmatic sense it reflects inefficiencies and wasted effort. The behaviour of the ESI about the MSO point might be explained in the following way:

- Moving down from an existing level of output to the MSO point will incur an increase in entropy from the change itself. However, this is more than offset by an increase in profitability and the ESI decreases.

- Moving down from the MSO point to a lower level of output also incurs an increase in entropy from the change itself but now profitability also reduces and there will be no offsetting effect. The ESI therefore increases.

The behaviour of nature

Nature, unlike much of humanity, does not actively seek competitive advantage from every situation. It tends to be indifferent in this regard. However, there will be some underlying objective that will determine its response to change, and it would seem to be that when faced with change, nature chooses a path that will result in a minimum increase in entropy. This would account for the stability of its long-term equilibrium with the managed landscape and hence, the importance of the MSO concept.

When faced with a binary choice as to how to respond to change (such as adapt or ignore), nature’s responses will follow a statistically random or normal distribution curve. However, if it does adapt, what results will depend on the starting point and the nature of the surrounding environment. This is a definition of ‘chaos theory’.

It is therefore probable that nature adapts chaotically to change. This might sound dramatic but all it signifies is that the outcome will be difficult to predict. Perhaps, surprisingly, order, in a localised form, comes out of chaotic behaviour under special conditions. This phenomenon is a form of ‘resonance’.

An example of this is the hexagonal structures to be found in the Giant’s Causeway in Ulster and this effect can be demonstrated in the kitchen when a saucepan of water is boiled. As the water cools there will be a point when the surface aligns into a jigsaw of hexagonal shapes, and it so happened that the Giant’s Causeway crystallised at this point.

The implications for de-stocking and re-wilding

If a farm is run-down to zero levels of output, nature will reclaim the property. However, there is no guarantee that this would take the land back to its ‘original state’, it will just be different and unpredictably so.

What results may well satisfy some people, but the intrinsic value of the change is impossible at this time to quantify. All that can be said is that if the landowner is satisfied, then they will have valued the change as being greater than any net income that will have been foregone.