Agriculture, both in the UK and globally, faces a significant period of change over the next two decades – not least through the ‘threat multiplier’ effects of climate change, turning what were often regarded as 1 in 100-year risk predictions into more regular and sometimes extreme events, including flooding, drought and pest inundations. This is in addition to the other challenges that farmers have to manage – many of which lie outside of their control.

In addition to climatic uncertainties, UK farmers and land managers face other issues:

- A new subsidy/grant regime (largely as a result of Brexit and changing trading conditions)

- Supply chain adjustments to meet new consumer demands

- Multiple policy and regulation changes

- Labour and skills shortages

- Market fluctuations

- Unexpected crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Agricultural land use in the UK, 2018

Farming activity covers some 17.0 million hectares (ha) (43 million acres), occupying around 69% of the UK landmass (see Figure 1). As such, it constitutes a vital part of the UK’s rural, agri-food and bioresource economy. Defra estimates that UK farming produced a total income from farming of £7.9 billion in 2022. Some 209,000 UK agricultural holdings (around 50% of which are under 20 ha) farm 70% of UK land.

Farming activity plays an important role in sustaining rural livelihoods and managing the local environment, as well as supplying the nation’s food needs. To continue to achieve this within changing economic and environmental conditions, farm businesses must remain viable, providing a living income for farming families and contributing significantly to the rural economy.

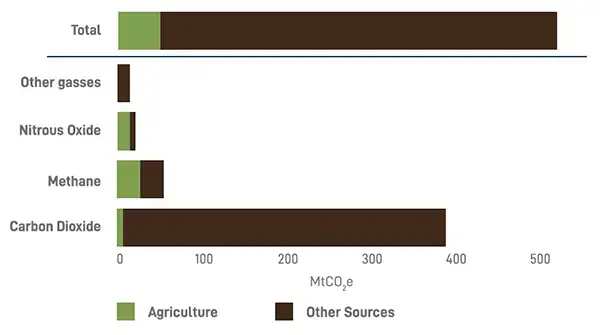

The National Farmers Union (NFU) reported in 2019 that greenhouse gas emissions from UK farms amounted to 45.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in 2018 – about 10% of the country’s total emissions.

UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions (2017) in CO2 Equivalents

Although not directly a greenhouse gas, agriculture is also responsible for 88% of the UK’s ammonia emissions, produced when organic fertilisers such as slurry, manure, sewage sludge, compost and digestate come into contact with air and warmth, and when organic and inorganic fertilisers are spread. Ammonia emissions adversely affect the quality of air, soil, water, ecosystems and biodiversity.

While agriculture urgently needs to address its emissions, it has the land area to be able to curb its emissions and sequester more carbon through improved nature-friendly farming practices. Farms are also able to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels by generating various forms of renewable energy. Farming is therefore a key part of the climate solution for rural Britain.

Following withdrawal from the European Union, UK farmers are moving away from a 40-year-old system of top-down area-based subsidy under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and towards different ‘post-Brexit’ agricultural policies covering the devolved regions of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – for example, the Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme which now applies in England.

This policy shift is an opportunity to drive more agroecological, regenerative farming and nature-based solutions on diverse types of farmed land, placing carbon sequestration and carbon reduction at the heart of future plans for farming, land management and the evolving food supply chain. The most up-to-date information can be found here for England, here for Wales, here for Scotland and here for Northern Ireland.

Farm business viability is key to farming’s critical functions in providing rural livelihoods, managing the environment and meeting emerging market demands. The core economic role of farming is to harness natural resources and to do so, where possible, at a commercial profit.

However, in 2019/20 to 2021/22, only the top 50% of farms made a profit from agriculture. Many others made little or no profit from their core agricultural activities – relying on additional income from farm or environmental diversification, along with the contribution from direct EU payment subsidies.

Following the UK’s exit from the EU, subsidies for land ownership and tenure have been phased out, and replaced by schemes that pay farmers and land managers to provide environmental goods and services alongside food production, such as the Environmental Land Management schemes in England, which began with the introduction of the Sustainable Farming Incentive in 2022. There have also been one-off grants to support farm productivity, innovation, research and development.

The nature of farm businesses is that they are ‘price takers’ (with limited ability to influence the value of their output) unless they sell to customers directly, for example by selling online or at markets and fairs.

There is consensus that British farmers produce food to some of the highest standards of hygiene, animal welfare and environmental protection in the world. As such, UK farms are well positioned to address the widening global demand for premium sustainably produced products.

Such opportunities are even more relevant following the UK’s exit from the EU, with opportunities for farmers and processors to be innovative in meeting demands from new international markets.

There is no doubt that over the next decade and beyond, farm businesses, operating within an ever-diversifying rural economy, will need to adapt to meet regulatory pressures and supply food and public goods whilst delivering against national targets on emissions reduction.

Agriculture needs to reduce emissions from production activities, and increase its potential to sequester carbon, both directly on land and indirectly, by increasing productivity and at the same time, reducing demand for land. To do this and to enable better planning and on-farm investment decision making, diverse UK farming businesses need to have a clear and dynamic vision for the way forward.

There is an appetite to understand the parameters for practical change at farm and water catchment level as part of land management activities, and to develop or refine technical and operational solutions which are available now or will emerge over the next few years.